This paper argues that viewing people as individuals rather than simply as members of a collective would be an important antidote to racism. This would require educating people to judge others, in accordance with Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, according to their character rather than their skin color. Such judgments require actual thinking, not just sense perception. They also require an understanding of emotions as automatic, subconscious value judgments. This requires that people learn the skill of introspection, starting with identifying what premises cause their reactions, such as when they first meet people (first impressions). It also requires that they recognize that when they have an emotion, they do not have to unthinkingly act on it. There are always action alternatives. It is important to recognize that people are not prisoners of their subconscious and have the power to re-program it by correcting false ideas, including racism, through reason.

The theme of this essay is: how racism (racial prejudice) could be reduced by teaching people how to evaluate other people as individuals, a process which requires that people understand their own emotions as well as how to judge other people. There are other groups, of course, but I focus on racism here because it is a major social issue and is in the news virtually every day.

Philosophically and politically racism is a form of collectivism. To quote Peikoff (1982, pp. 7–8): “Collectivism is the theory that the group (the collective) has primacy over the individual. Collectivism holds that in human affairs the collective—society, the community, the nation, the proletariat, the race, etc.—is the unit of reality and the standard of value. On this view, the individual has reality only as part of a group….” Psychologically, this means that the core of one’s identity is not one’s nature as an individual but rather as a member of a racial group. Today the “individual” often seems not to be worthy of attention; collective members may be viewed as interchangeable units. Or, if one focuses on (or advocates focusing on) just individuals, one may be accused of being racist.

What is the problem with this picture? First, consider the obvious: all collectives

are comprised of individuals. A group or collective is not an actual entity but an abstraction. For example, there is no such entity as a “team” other than as a group of individuals pursuing a common goal. To quote Albert Bandura, “There is no such thing as a disembodied group mind….” (2016, p. 13). Of course, individuals who have and share relevant knowledge and skill and work together based on a common purpose can often accomplish more than one person acting alone. But the members are still individuals. Similarly, a society is an abstraction: a group of individuals living in the same geographical location and, in the case of a country, living under a single government and ideally sharing common values. Race too is an abstraction (a collective noun) based on the existence of individuals with similarities in skin color and other physical features.

This does not deny that individuals in a collective or group may have strong emotional connections due to common values; obviously they do. But the connections are between individual members. Without individual members, there would be no group or team or society or race (however defined) at all. As Bandura notes, people’s bodies and minds are not physically connected. Common values held by groups or sub-groups are not always positive. The values can include prejudices, stereotypes and biases with respect to other groups, whether local or national, and so it has been throughout history. Relatively speaking, America is arguably the most successful country in the world in integrating people who differ in race, nationality, religion and culture. We may be one of the few countries in history, to my knowledge, that fought a civil war based on the moral principle that everyone has equal rights, as opposed to one gang deposing another until another gang deposes it.

But the civil war was only a beginning. Millions of people thought blacks were subhuman and thus did not deserve rights. Fully implementing the Declaration of Independence was a titanic struggle, and it is not over yet.

If one accepts the doctrine of genetic determinism in the realm of ideas, then, of course, it would make sense to view every member of a collective as the same on the grounds that they have all been pre-programmed to think and act in the same way. But I think the evidence is overwhelmingly in line with the views of Aristotle and John Locke who argued that people are born tabula rasa, without mental content such as specific values or beliefs. Ideas, including moral principles, are not inborn; they are acquired. A variant on this is social determinism, “conditioning” by what groups one belongs to. Conformity, of course, is a real social-psychological phenomenon that is clearly related to role modeling (Bandura, 1986), but every person does not conform; people have the power to think for themselves (Locke, 2018). Further. not every person in a given group, such as a racial group, has had the same experiences.

Individualism

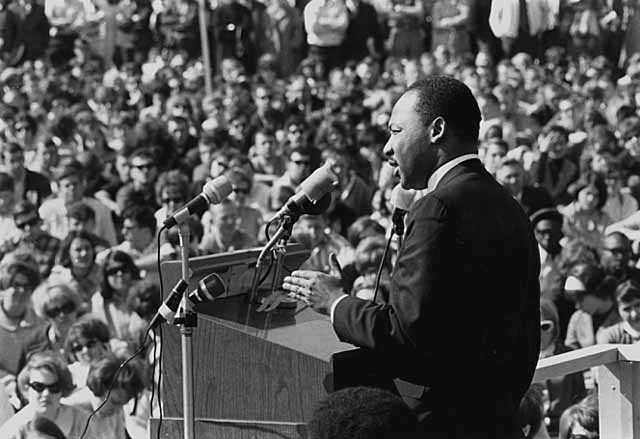

What would be a more objective way of looking at people than as racial clones? My favorite quote is from Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech where he expresses the hope that children (implying all people) “will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” Character, I submit, and I think King would agree, is individual; it is not determined by race. So why not judge individuals based on their own attributes and characteristics? The goal is not literal color blindness (skin color is self-evident to sense perception) but character awareness. Skin color, though real, should not be viewed as primary.

It is fair to ask: Why do people not routinely work to think of others in terms of their individual character? One reason is that we are encouraged today, as noted above, not to look at the individual qua whole individual but mainly, if not only, as a member of the racial collective to which they belong. A second reason is that drawing conclusions from skin color is much easier than character judgment. It is cognitively effortless precisely because skin color is automatically perceived. Sense perception is the result of unconscious processes: the physical response of sense organs to energy and the integration of signals by the brain. If one looks only at skin color without choosing to expend the effort of conscious thought about the meaning of our perceptions, this allows whatever subconscious stereotypes a person might have to take over the process of evaluation in the form of an emotion. (More on this below.)

Subconscious appraisals are not confined to skin color. Whenever we meet someone, we form first impressions. We routinely experience subconscious associations based, for example, on physical attractiveness, dress, tone of voice, body language including eye contact, movement and gestures, gender, and, of course, race. We may draw automatic conclusions about character immediately from these first impressions—but such conclusions may be wrong. If one stops mentally with sense perception and its subconscious associations, this short-circuits the thinking process. Collectivism itself is a form of stereotyping: everyone in the group is assumed to be the same. But this is not so; everyone is a unique combination of attributes and characteristics.

What would happen if we learned or were trained to see everyone as an individual? Why not individuality training? Why not help people learn how to go about judging other, individual, people objectively? But how should we judge other people? Obviously based on their words and actions, but we have to learn how to put the pieces together. This requires mental work.

Emotions

An important starting point for individuality training would be to teach people to understand their emotions, an important life skill. After over 50 years in the field of psychology, I have concluded that most psychologists do not understand the root of emotions even when they talk about them. They often view an emotion as some form of psychological primary that is beyond deeper understanding or analysis. They talk about emotional labor and emotional expression but not about what emotions are.

What, then, are emotions? In my view, emotions are the form in which one experiences automatic, subconscious judgments, including value judgments, which means they come from automatic appraisals based on subconsciously held ideas. Arnold (1960) was one of the first to understand this by arguing that emotions involve implicit judgments. But it does not follow from this that people are necessarily dominated by their subconscious (a regression to Freudianism by which by I mean being dominated by the unconscious). On the contrary, if emotions come from subconscious ideas, such ideas can be identified through introspection and the ideas can be questioned and changed (Locke, 2009a).

It is very unfortunate that introspection has been virtually banned as a scientific method, based on an outdated view of the philosophy of science (Locke, 2009b). I base this on decades of observing that virtually no highly regarded professional journal publishes papers in which the core evidence was introspective. Of course, researchers smuggle in self-reports, but these virtually never ask people to identify the appraisal process that caused their emotions.

Before we get to changing ideas, I will start with a simple example of how the

automatic process works. Let’s say you are hiking in the deep woods and encounter a grizzly bear, and worse yet, one with cubs. The bear is growling at you. You have no weapon and there is no nearby tree to climb. The emotion you experience is fear. What is this based on? You have stored in the subconscious, i.e., memory, that there are grizzly bears, that they are large and strong animals, that they sometimes attack people and that they are especially aggressive when they are with cubs, and that you are defenseless. Further, you value your life. Your subconscious automatically and instantaneously integrates your knowledge of grizzlies, the perceived situation and your love of your own well-being (your values). That causes you to feel fear. The emotion of fear is because you appraise the situation as representing a physical threat. You can do mental experiments to verify the causal role of ideas in this example. What if you had no knowledge of grizzly bears? What if the bear and cubs were seen as moving away? What if you had an easily climbable tree three feet away? What if you had a (probably illegal) gun and knew how to use it? What if there was a 25-foot fence or deep ditch between you and the bears? What if you hated your life because you were living in excruciating pain from cancer and wanted to die? These factors would change the appraisal so that there would be no (or very minimal) perceived threat and thus no, or greatly reduced, fear or even relief. Every emotion (brain miswirings or damage and drugs aside) is caused by a specific type of subconscious appraisal (Locke, 2009a). For example, anger is a response to perceived injustice; guilt, to the belief that you did something immoral; anxiety, to self-doubt and uncertainty; love, to viewing something or someone as a value; happiness, to believing one has attained a successful state of life. (Complex emotions can involve multiple appraisals.)

Teachers can validate the basic idea with a simple class experiment—one I used many times. One day as class is starting, you announce that there will be an unannounced quiz and that it will count as one course grade. Then have your TA appear to be handing out quiz papers. Listen to the groans for a few second and then say you were kidding. Ask the students what they were feeling after the announcement. It is always two emotions: anger because they saw the quiz as unfair and anxiety because they thought it might hurt their grade. (To avoid even a small deception, you can ask the students what they would feel if you had made the announcement.)

An important point needs to be made here about the subconscious. The brain never stops functioning unless you are dead. The subconscious makes automatic associations all day, every day (and even at night). It is “judgmental” 24/7 whether you like it or not. So you experience appraisals and thus emotions continuously, though most are not strong or compelling, so you ignore them. But to know and understand what is going on, what the emotion at a given time is and what caused it, you would have to choose to consciously focus on the appraisal process, which requires introspection (technically, it is introspection done backwards in time). Obviously, you cannot do this all the time, because you need to regulate your everyday actions and may even have to suppress emotions in order to get certain things done. Introspection, focusing inwards on the content and processes of your mind, is done by choice. Bandura (1997) noted that there is such a thing as cognitive self-efficacy, which involves developing mental skills.

Now consider first impressions of and reactions to other people. What do we need to do to see the individual beyond skin color? Start by noticing that we have automatic responses. First impressions will typically fall into one of three categories: positive, negative or neutral (no particular value judgment even if there are factual observations such as: X is shy, Y seems to like discussing history). One’s first impression, of course, may change in the course of a single meeting. If the impression is positive, what caused it? What inferences are being drawn from physical appearance (looks)? Going past that, does the person seem friendly, sincere, interesting (to you)? Do you seem to share any common values? Are there any “red flags”? Let’s say the individual appears self-confident, but you notice that the person is persistently boastful (often a sign of narcissism and self-doubt). Do they dominate the conversation? Do they ignore whatever you have to say? Are they defensive? Hostile? Your first impression could change from positive to negative.

If your first impression was negative, what set you off? Again, maybe their looks but what else is there? Maybe you did not like how they dressed. Did they have body odor? Did they seem arrogant or cynical or unhappy? Did they fail to look you in the eye? Were they too quiet and seemingly unable to support a conversation? Did you change your appraisal when you realized the other person was shy but could be brought out by asking questions? Did you discover that they had virtues or values that you agreed with but that were not immediately apparent? Your first impression could change from negative to positive. If the first impression was neutral, it may mean that you were not particularly struck by anything, however, more contact could change that.

Consider an example of an emotion based on a first impression, an appraisal based on very limited information. It relates an experience I had during the writing of this article. I belong to a gym at a nearby private college. The college is liberal, mostly white but with a few minority students. When you enter, your membership is checked by a monitor who is typically a student. The monitor makes sure you swipe your membership card. At the desk on one visit was a physically attractive, athletic-looking black man. He was slouching in his chair, with his feet on the desk, looking unhappy and was not friendly, totally unlike the typical monitor. He never acknowledged or looked at anyone going in or coming out. No eye contact. He was glancing vaguely at his cell phone but not engrossed in anything. My emotional reaction was mildly negative: “What’s the matter with this guy?” I decided to see what would happen if I engaged him in conversation. I started by asking if he was a student, which he was. His face lit up and his whole demeanor changed. We talked for a few minutes about his major and his career aspirations. He loved the college, was in a challenging major, which he liked, and had specific career plans for when he graduated. My mildly negative first impression changed to positive. “This guy is purposeful and loving his life.” I do not know anything about this man’s personal life, but the point of this anecdote is that my automatic reaction changed as a result of new knowledge I acquired, based on consciously directed communication. Obviously, if I had gotten to know him better, there would have been additional appraisals and corresponding emotions, based on additional knowledge.

A note about ideology. If an individual holds to a certain ideology and one understands that ideology, it is totally valid to take that into account in making character judgments. A Nazi, Communist or ISIS supporter, anyone who has contempt for individual rights and thus human life, is morally very different than an advocate of rights. Character matters.

Moving past first impressions, how does one judge an individual, say an acquaintance or a friend, over a longer time period? How does one get past these impressions that will usually not give one the full story on another? Here one needs to look for patterns, which basically means a sampling of words and actions in various contexts. Has this individual been honest? Interested in the truth? Do they want to learn? Take facts seriously? Are they considerate? Nice? Manipulative or narcissistic? Criminal? Violent? Sincere? Curious? Interesting to be with? Friendly? Hostile? Moody? Snobbish? Stimulating? Boring? Abrasive? Genuine? Have they changed over time? How? Do they have a healthy or unhealthy lifestyle? Are there any common values or intellectual interests? Are the personalities compatible? Is there mutual emotional and/or intellectual visibility (see Locke & Kenner, 2011)? Do they act differently when others are present, compared to one-on-one? Why? Are they role-playing?

This does not mean every attribute should be weighed equally. I would agree with King that one should put character first. Bad character can undermine desirable traits. Imagine a person who is intelligent but dishonest. The intelligence will be used to deceive and manipulate people. If there are discrepancies between words and deeds, treat the deeds as being representative of the individual’s real character. An example: keeping promises, which reflects integrity. Talk itself, as the saying goes, is cheap. Observe that all these judgments require mental focus: looking at facts, tying information together, reaching conclusions or revising them, understanding one’s emotional responses. In sum: thinking. Once one commits to functioning at this level, skin color becomes incidental or, one would hope, greatly reduced in importance. Of course, there are many levels of friendship, that is, degrees of intimacy. This will depend on the degree of compatibility and the depth of the shared values.

Emotions and Action

An important point needs to be made about emotions in relation to action. Inherent in emotional responses are felt action tendencies (Arnold, 1960). Action is required for survival. People are naturally motivated to approach, protect and retain positively appraised objects and to avoid, disable, oppose or destroy negatively appraised objects. If values were only held as intellectual abstractions, if sensory and emotional pleasure and pain did not exist, people would be indifferent to action. Imagine if a cave man, upon meeting a sabre tooth tiger, said to himself, “Hmm—that is a sabre tooth tiger. I have been told it is dangerous. It might kill me. I wonder if death is a bad thing? Should I do something?” Oops, too late. If cavemen did not respond (and rapidly) to the sight of a predator, evolution might have been badly slowed or stopped.

However, it does not follow that emotions automatically determine action. There are, of course, people who have developed over time the habit of being impulsive. (It is very unfortunate that modern culture, facilitated by technology, seems to encourage this.) Breaking deeply ingrained habits can be difficult, but it is not impossible. There might be situations in which it is very hard to act or not act, but under most circumstances people can make choices. Imagine that your boss at work treats you unjustly. Consider how many action alternatives there are, e.g., say nothing, verbally protest, quit on the spot, use violence, see a lawyer, consult with colleagues, complain at a higher level, leave work for the day, get drunk, look for a new job, etc. People have the power to consider and reconsider their assessment of situations that involve noticeable emotions. They can consider options and make a judgment about the best course of action, including taking no action until the emotional level has cooled down. Choosing the best course of action involves thought and problem solving.

Some Observations about the Dual Process Model

It is important, in view of the above discussion, to relate it to the dual process model, publicized, for example, by Kahneman (2011) and others. This model contrasts subconscious processing, which is lightening fast, with conscious processing, such as is involved in planning and problem solving, which is slow and deliberate. This distinction is totally valid as far as it goes. But what is much less often mentioned is that the conscious and subconscious are interacting everyday, all day. So, the implicit idea that there are two separate selves (which stems at root from Plato) that may be at war with one another leading to endless decision errors is quite misleading. If our decision-making is as poor as is sometimes implied, the human race should have become extinct long ago. People do often make rational decisions!

The core function of the subconscious is storage, that is, automatization. The conscious mind affects what is stored and regulates purposeful action. But they work together, and both are required for survival. Imagine a person who could think but could never retain anything or a person who stores everything but could not make purposeful choices among the millions of stored ideas. To use a simple example, consider holding a conversation. To do this one would have had to automatize the meanings of the words used, some connections between them, such as subject and verb, and linguistic structure. Without this, conversation, and learning from others, would be impossible. Automatization leaves the mind free to focus consciously on the meaning of the pattern of words, which is somewhat different in every conversation. This in turn can lead to subconscious filing (“Oh, that could be important”) and more conscious processing (“This needs more thought”). Bandura (1997) has discussed at length the automatization of skills including the mergerization of various mental processes guided by conscious self-regulation. If one chooses to think, one can program the subconscious by filing certain ideas (Locke, 2018). If not, if one drifts without thought, the subconscious files at random based on what one happens to pick up from the environment, usually a melange of unprocessed ideas from others—often for the worse. If one detects a conflict, viz., “I should not be prejudiced but I still feel it,” one can identify the error (“I did not even look at them as an individual person”) or the motive (“I wanted to feel superior”) if one introspects well.

To resolve such a conflict, one has not only to have self-insight but also be motivated to change, which in this case revolves around the virtues of justice and integrity. This brings us to the issue of moral values. Bandura (2016) has written at length about the fact that people commit immoral acts by a process of disengagement through various forms of rationalization. Though his claims have merit, this is not the whole story. Some people have no morals to disengage from. They do whatever they feel like doing. In philosophy this is known as pragmatism: doing whatever “works” or makes one feel good at the time (e.g., see Peikoff, 1982, Chapter 6). Many people claim to hold certain virtues, but they are only feelings, not principles that consistently guide one’s choices. What are the implications here for racism? Saying that one is not racist and that one treats everyone fairly proves nothing. One’s operative principles are expressed in how one acts.

This brings us back to the dual process theory once more. People can have conflicts between the conscious and the subconscious. They have the power, up to a point, to act against their subconscious premises. One does not have to act on automatized premises and emotions. An individual who has some racist premises and has not yet chosen to or been able to fully identify or correct them still has the power to act politely and respectfully toward others through conscious self-direction. People should not be made to feel guilt or self-doubt because they might have hidden premises, e.g., “You say you are not racist but deep down you probably are.” Fairness requires that people be judged by others based on their observable actions not based on suspicions about what might be stored in their subconscious.

This does not mean that people should be indifferent to their own emotions. If one finds it necessary to frequently act contrary to certain emotions, it means that one’s subconscious and conscious ideas are in conflict, e.g., being black is OK vs. being black is not OK. Without correction, such contradictions can put people at war with themselves, an unstable and stressful condition. This can undermine self-control; the result can be inconsistencies in behavior. One would have to be continually on guard against dropping one’s guard. The ideal is a harmony between reason and emotion because one’s conscious and subconscious ideas are in sync.

Racism

Now let’s turn to race using a fictional example. Racism is based on a collectivistic assumption, i.e., that all members of a given race have a certain (and not admirable) character. Such an assumption must involve a thinking error, specifically overgeneralization. Bill, a white male, meets John, a black male, at a party. Let’s say the first emotional response for each individual is negative. If Bill introspects, he might catch himself thinking, “Oh, oh, a black guy; he probably will not like me and will accuse me of being a racist.” John might introspect and think, “Oh, oh, a white guy. He will probably not like me because he is racist.” Observe here the only facts involved so far pertain to skin color. The negative emotions are due to subconscious, collectivist associations or assumptions, e.g., all blacks hate or distrust whites, all whites hate or distrust blacks. But what would happen if Bill and John decided to learn more about each other as individuals by engaging in a conversation? “Are you a student? What is your major? Why did you choose it? Do you have any career plans? Do you work? In what field? Where are you from? What are your outside interests? What kind of art or music do you like? Do you like to read books? What kind? Do you have a philosophy for living? What is it? What are your life aspirations, etc.?” I am not saying to give everyone you meet the third degree; the point is to learn about who they are as individuals.

This does not mean that all whites and blacks will become best friends. But the same is true within racial groups. Aristotle said the highest or most intimate type of friendship is a friendship of virtue. It is based on people admiring each other’s character as Martin Luther King recommended. Of course, friendship (and romance) involves more than just virtue. There are many degrees of friendship based on common but morally neutral values (e.g., how you spend your time), interests, personalities and abilities. But none of these attributes are built into any one race.

Teaching the Young

Ideally people should be taught to judge others as individuals from a young age. Young people are (we hope) in the process of developing themselves by choosing their philosophies of life, by acquiring virtues, by considering a wide range of ideas, by constant learning, by interaction with others. They need to be inspired to think and not be pressured to conform to any racist status quo. They need to discover that everyone is an individual and why generalizing from skin color, positively or negatively, is, most fundamentally, a philosophical error—a false generalization.

To quote Ayn Rand (1964, p. 147), a renowned champion of individualism: “Racism is the lowest, most crudely primitive form of collectivism. It is the notion of ascribing moral, social or political significance to a man’s genetic lineage—the notion that a man’s intellectual and characterological traits are produced and transmitted by his internal body chemistry. Which means, in practice, that a man is to be judged, not by his own character and actions, but by the characters and actions of a collective of ancestors.”

Children have to learn about individualism in layers. At an early age they could be taught to start with questions such as: Who do you like at school? Why? Who do you dislike? Why? This is the beginning of introspection. The first answers might be simply: That person is nice to me. That person is mean to me. As they grow cognitively, they can learn to make more complex character judgments, e.g., about honesty, integrity, fairness, etc.

Is Teaching Hopeless?

Alleged discoveries based on measures of implicit (subconscious) bias challenge the notion that people can overcome bias through thought. A leading researcher, psychologist Mahzarin Banaji claims in Observer, the journal of the Association of Psychological Science (Drew, 2018, p. 15), “The conscious level of the mind is obliged to use what the automatic [subconscious] level provides to it, and in this way the lower level controls conscious perception, thought, and judgment.” Let’s examine this bizarre claim. The implication is that the conscious mind has no function in life, that we are passive victims of what we have stored in memory and that’s it. What is missing here? The facts that it is the conscious mind that gathers and evaluates the information that is stored; that the conscious mind has the power to identify and question what is stored; that the subconscious is fundamentally passive in that it works by association, whereas the conscious mind is active and guides our search for an integration of knowledge and directs the thousands of decisions and associations that we make every day of our lives. As a form of determinism, Banaji’s assertion of subconscious determinism is also self-refuting (Locke, 2018). How would she know whether the subconscious is feeding her false information about her own experiments? Given Banaji’s premise, going to school and college in order to learn to think would seem to be a waste of time.

It is simply not the case that conscious, open discussion of racism is impotent. Pinker (2018, Chapter 15) has documented that racism has been steadily declining on the U.S. over the last 20 or so years. He attributes this mainly to education (see his Chapter 16). One can infer from this that conscious learning and exposure to rational thought is the major contributor to this trend. Thus, we are not helpless prisoners of our subconscious ideas. We can program and re-program the subconscious by thinking.

Should Young People Be Exposed to Racist Arguments?

Absolutely, especially high school and college students. How else will they learn what is wrong with such arguments? Being told you had better not be racist may get some people to conform out of fear of disapproval, but how much better for them to learn why it is wrong and how to judge people based on a rational thought process. Nor is it helpful to try to make people feel guilty for their alleged subconscious premises. Teach them to understand their specific emotions by introspection and check the validity of the ideas behind them, such as collectivism. People need to learn not just the negative, the irrationality of collectivism and racism, but the positive alternative, individualism. Individualism is the base of social justice when it comes to evaluating others.

Aristotle said than every man (person) by his nature desires to know. But it is obvious that there are exceptions. We all know that some people do not want to know and have a vested interest in false ideas, perhaps to prop up their illusion of self-esteem by denigrating others. But such people can be intellectually opposed. Bandura (1986) has documented the power of role models and what makes them work. Educating people to understand their emotions and to look at people as individuals has the potential to greatly reduce racial prejudice.

References

Allport, G., 1954, The nature of prejudice. Boston: Addison-Wesley.

Arnold, M., 1960,.Emotion and personality: Vol. 1. Psychological aspects. New York: Columbia University Press.

Bandura, A., 1986. Social foundations of thought and action. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A., 1997. Self efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman.

Bandura A., 2016. Moral disengagement. New York: Worth (Macmillan).

Drew, A., 2018, “Mahzarin Banaji and the implicit revolution.” Association for Psychological Science: Observer, 38 (2), 15–19.

Kahneman, D. 2011. Thinking fast and slow. New York: Macmillan.

Locke, E. A., 2009a, “Attain emotional control by understanding what emotions are.” In E. A. Locke (ed.) Handbook of principles of organizational behavior, 2nd edition. New York: Wiley.

Locke, E. A.., 2009b. “It’s time we brought introspection out of the closet”. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4, 24–25.

Locke, E. A., 2018, The illusion of determinism: Why free will is real and causal. Los Angeles, CA: Edwin A. Locke

Locke, E. A. & Kenner, E., 20ll, The selfish path to romance. Doylestown, PA: Platform Press.

Peikoff, L. (1982) The ominous parallels. New York: Stein and Day.

Pinker, S., 2018, Enlightenment now. New York: Viking.

Rand, A., 1964. Racism. In A. Rand (ed.) “The virtue of selfishness.” New York: Signet.