It is an old adage that there are lies, damn lies and then there are statistics. Nowhere is this truer that in the government’s monthly Consumer Price Index (CPI) that tracks the prices for a selected “basket” of goods to determine changes in people’s cost-of-living and, therefore, the degree of price inflation in the American economy.

On August 19th, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released its Consumer Price Index report for the month of July 2014. The BLS said that prices in general for all urban consumers only rose one-tenth of one percent for the month. And overall, for the last twelve months the CPI has only gone up by 2 percent.

A basket of goods that had cost, say, $100 to buy in June 2014 only cost you $100.10 in July of this year. And for the last twelve months as a whole, what cost you $100 to buy in August 2013, only increased in expense to $102 in July 2014.

By this measure, price inflation seems rather tame. Janet Yellen and most of the other monetary central planners at the Federal Reserve seem to have concluded, therefore, that they have plenty of breathing space to continue their aggressive monetary expansion when looking at the CPI and related price indices as part of the guide in deciding upon their money and interest rate manipulation policies.

Overall vs. “Core” Price Inflation

The government’s CPI statisticians distinguish between two numbers: the change in the overall CPI, which rose that 2 percent for the last year, and “core” inflation, which is the rate of change in the CPI minus food and energy prices. Leaving these out, “core” price inflation went up even less over the last twelve months, by only 1.9 percent.

The government statisticians make this distinction because they argue that food and energy prices are more “volatile” than many others. Fluctuating more frequently and to a greater degree than most other commonly purchased goods and services, they can create a distorted view, it is said, about the magnitude of price inflation during any period of time.

The problem is that food and energy costs may seem like irritating extraneous “noise” to the government number crunchers. But to most of the rest of us what we have to pay to heat our homes and put gas in our cars, as well as buying groceries to feed our families, is far from being a bothersome distraction from the statistical problem of calculating price inflation’s impact on our everyday lives.

Constructing the Consumer Price Index

How do the government statisticians construct the CPI? Month-by-month, the BLS tracks the purchases of 6,100 households across the country, which are taken to be “representative” of the approximately 320 million people living in the United States. The statisticians then construct a representative “basket” of goods reflecting the relative amounts of various consumer items these 6,100 households regularly purchase based on a survey of their buying patterns. They record changes in the prices of these goods in 24,000 retail outlets out of the estimated 3.6 million retail establishments across the whole country.

And this is, then, taken to be a fair and reasonable estimate – to the decimal point! – about the cost of living and the rate of price inflation for all the people of the United States.

Due to the costs of doing detailed consumer surveys and the desire to have an unchanging benchmark for comparison, this consumer basket of goods is only significantly revised about every ten years or so.

This means that over the intervening time it is assumed that consumers continue to buy the same goods and in the same relative amounts, even though in the real world new goods come on the market, other older goods are no longer sold, the quality of many goods are improved over the years, and changes in relative prices often result in people modifying their buying patterns.

The CPI vs. the Diversity of Real People’s Choices

The fact is there is no “average” American family. The individuals in each household (moms and dads, sons and daughters, and sometimes grandparents or aunts and uncles) all have their own unique tastes and preferences. This means that your household basket of goods is different in various ways from mine, and our respective baskets are different from everyone else’s.

Some of us are avid book readers, and others just relax in front of the television. There are those who spend money on regularly going to live sports events, others go out every weekend to the movies and dinner, while some save their money for an exotic vacation.

A sizable minority of Americans still smoke, while others are devoted to health foods and herbal remedies. Some of us are lucky to be “fit-as-a-fiddle,” while others unfortunately may have chronic illnesses. There are about 320 million people in the United States, and that’s how diverse are our tastes, circumstances and buying patterns.

Looking Inside the Consumer Price Index

This means that when there is price inflation those rising prices impact on each of us in different ways. Let’s look at a somewhat detailed breakdown of some of the different price categories hidden beneath the CPI aggregate of prices as a whole.

In the twelve-month period ending in July 2014, food prices in general rose 2.5 percent. A seemingly modest amount. However, meat, poultry, fish and egg prices increased, together, by 7.6 percent. But when we break this aggregate down, we find that beef and veal prices increased by 10.4 percent and frankfurters went up 6.9 percent, but lamb rose by only by 1.7 percent. Chicken prices increased more moderately at 2.7 percent, but fresh fish and seafood were 8.8 percent higher than a year earlier.

Milk was up 5.4 percent in price, but ice cream products decreased in price by minus 1.4 percent over the period. Fruits increased by 5.7 percent at the same time that fresh vegetable prices declined by minus 0.5 percent.

Under the general energy commodity heading, prices went up by 1.2 percent, but propane increased by 7.3 percent in price over the twelve-month period, while electricity prices, on the other hand, increased by 4 percent.

So why does the overall average of the Consumer Price Index seem so moderate at a measured 2 percent, given the higher prices of these individual categories of goods? Because furniture and bedding prices decreased by minus 3.1 percent, and major appliances declined in price over the period by minus 6.2. New televisions went down a significant minus15 percent

In addition, men’s apparel went down a minus 0.2 percent over the twelve months, but women’s outerwear rose a dramatic 12.3 percent in the same time frame. And boys and girls footwear went up, on average, by 8.2 percent.

Medical care services, in general, rose by 2.5 percent, but inpatient and outpatient hospital services increased, respectively, by 6.8 percent and 5.6 percent.

Smoke and Mirrors of “Core” Inflation

These subcategories of individual price changes highlight the smoke and mirrors of the government statisticians’ distinction between overall and “core” inflation. We all occasionally enter the market and purchase a new stove or a new couch or a new bedroom set. And if the prices for these goods happen to be going down we may sense that our dollar is going further than in the past as we make these particular purchases.

But buying goods like these is an infrequent event for virtually all of us. On the other hand, every one of us, each and every day, week or month are in the marketplace buying food for our family, filling our car with gas, and paying the heating and electricity bill. The prices of these goods and other regularly purchased commodities and services, in the types and combinations that we as individuals and separate households choose to buy, are what we personally experience as a change in the cost-of-living and a rate of price inflation (or price deflation).

The Consumer Price Index is an artificial statistical creation from an arithmetic adding, summing and averaging of thousands of individual prices, a statistical composite that only exists in the statistician’s calculations.

Individual Prices Influence Choices, Not the CPI

It is the individual goods in the subcategories of goods that we the buying public actually confront and pay when we shop as individuals in the market place. It is these individual prices for the tens of thousands of actual goods and services we find and decide between when we enter the retail places of business in our daily lives. And these monetary expenses determines for each of us, as individuals and particular households, the discovered change in the cost-of-living and the degree of price inflation we each experience.

The vegetarian male who is single without children, and never buys any types of meat, has a very different type of consumer basket of goods than the married male-female couple who have meat on the table every night and shop regularly for clothes and shoes for themselves and their growing kids.

The individual or couple who have moved into a new home for which they have had to purchase a lot of new furniture and appliances will feel that their income has gone pretty far this past twelve months compared to the person who lives in a furnished apartment and has no need to buy a new chair or a dishwasher but eats beef or veal three times a week.

If the government were to impose a significant increase in the price of gasoline in the name of “saving the planet” from carbon emissions, it will impact people very differently depending up whether an individual is a traveling salesman or a truck driver who has to log hundreds or thousands of miles a year, compared to a New Yorker who takes the subway to work each day, or walks to his place of business.

It is the diversity of our individual consumer preferences, choices and decisions about which goods and services to buy now and over time under constantly changing market conditions that determines how each of us are influenced by changes in prices, and therefore how and by what degree price inflation or price deflation may affect each of us.

Monetary Expansion Distorts Prices in Different Ways

An additional misunderstanding created by the obsessive focus on the Consumer Price Index is the deceptive impression that increases in the money supply due to central bank monetary expansion tend to bring about a uniform and near simultaneous rise in prices throughout the economy, encapsulated in that single monthly CPI number.

In fact, prices do not all tend to rise at the same time and by the same degree during a period of monetary expansion. Governments and their central banks do not randomly drop newly created money from helicopters, more or less proportionally increasing the amount of spending power in every citizen’s pockets at the same time.

Newly created money is “injected” into the economy at some one or few particular points reflecting into whose hands that new money goes first. In the past, governments might simply print up more banknotes to cover their wartime expenditures, and use the money to buy armaments, purchase other military supplies, and pay the salaries of their soldiers.

The new money would pass into the hands of those selling those armaments or military supplies or offering their services as warriors. These people would spend the new money on the particular goods and services they found desirable or profitable to buy, raising the demands and prices for a second group of prices in the economy. The money would now pass to another group of hands, people who in turn would now spend it on the market goods they wanted to demand.

Step-by-step, first some demands and some prices, and then other demands and prices, and then still other demands and prices would be pushed up in a particular time-sequence reflecting who got the money next and spent in on specific goods, until finally more or less all prices of goods in the economy would be impacted and increased, but in a very uneven way over time.

But all of these real and influencing changes on the patterns of market demands and relative prices during the inflationary process are hidden from clear and obvious view when the government focuses the attention of the citizenry and its own policy-makers on the superficial and simplistic Consumer Price Index.

Money Creation and the Boom-Bust Cycle

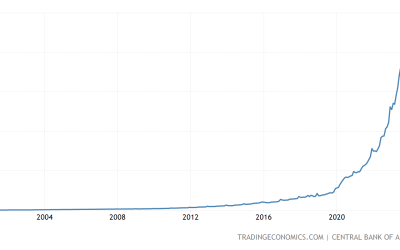

Today, of course, virtually all governments and central banks inject new money into the economy through the banking system, making more loanable funds available to financial institutions to increase their lending ability to interested borrowers.

The new money first passes into the economy in the form of investment and other loans, with the affect of distorting the demands and prices for resources and labor used in capital projects that might not have been undertaken if not for the false investment signals the monetary expansion generates in the banking and financial sectors of the economy. This process sets in motion the process that eventually leads to the bust that follows the inflationary bubbles.

Thus, the real distortions and imbalances that are the truly destabilizing effects from central banking inflationary monetary policies are hidden from the public’s view and understanding by heralding every month the conceptually shallow and mostly superficial Consumer Price Index.