Japanese entrepreneur Yusaku Maezawa has a vision for a world without money. In a recent interview with Russian news agency TASS the clothing-tycoon-turned-space-tourist with a net worth of $1.9 billion explained why he believes capitalism is unsustainable and money is the cause of all the world’s major problems:

I think there are a lot of problems with capitalism. . . . It is not sustainable, I think. Capitalism should be changed to something new, very soon. . .

Someday, money will disappear suddenly from this world. Of course, my bank account will be zero. Everyone’s bank account will be zero. And everything in stores [will be] for free. So, everyone can take everything for free from stores. If you love cars you can ride a Ferrari as soon as you want—for free.

Money is an enemy of the people, so money should disappear . . . And if money disappears, maybe every kind of war will also disappear and all crime [is] caused by money. So, money will disappear from this world, and every [type of] crime will also disappear.[1]

What will replace money in Maezawa’s vision of the future? Aside from free Ferraris, he doesn’t say, but he does promise to make a movie in the near future setting out his ideas.

The most obvious alternative to money is a barter system, where people simply trade objects and services directly with one another. If I want some bread, I need to find someone who has bread and offer him something he wants. What do I have that the man with the bread might want? Maybe nothing. Maybe only something I don’t want to part with. Money solves this problem. Instead of having to find something that each person I need to trade with wants, I can give each of them some money, and they can use that to get whatever they want. I, in turn, get my money by offering other people goods and services they want. Instead of having to find matching items to trade with each individual person, money offers a medium of exchange that everybody can use for their unique needs.

But Maezawa doesn’t mention trading anything for that Ferrari. He says you’ll just walk into the shop and collect it for free. This raises all sorts of questions:

- Why would Ferrari build a car if they won’t get anything in return for it?

- How would they get the materials needed to build it?

- How would they get people to build it?

- If capitalism is to be replaced with something different, will the government build and provide the car? If so, would they build anything even closely resembling a Ferrari?

Clearly, this interview does not provide enough detail to understand Maezawa’s vision. So let’s look at some more developed ideas about how a moneyless future might work.

The Resource-Based Economy

[A resource-based economy] is an economic system that represents a conceptual shift from a situation in which we think we are building things through money, to a situation where we understand that in order to build and manufacture anything, resources and technological knowledge are needed. If I have wood, tools and know-how, I can build a table without money, but if I’m on the moon, and I have no resources, but I have a suitcase with a million dollars—I can not build a table.—Jacque Fresco

Jacque Fresco, who described himself as a “social engineer,” was the founder of The Venus Project, an organization set up to promote a new kind of society “Beyond Poverty, Politics, and War.” Key to this vision is transitioning from a money-based economy to what Fresco calls a “resource-based economy.” The basic idea is that money is not what people need to create things and live fulfilling lives—resources are. Fresco argues that we should replace a society based on monetary exchange with a socially engineered society in which allocation of resources is centrally controlled, machines free up our time for leisure and personal development, and people create products simply out of a desire to improve the world around them. According to The Venus Project website:

In a Resource Based Economy all goods and services are available to all people without the need for means of exchange such as money, credits, barter or any other means. For this to be achieved, all resources must be declared as the common heritage of all Earth’s inhabitants. Equipped with the latest scientific and technological marvels, humankind could reach extremely high productivity levels and create an abundance of resources.[2]

This idea is based on a gigantic assumption: That people would produce the “scientific and technological marvels” necessary to create such a level of abundance for all goods and services to be available to all people without any form of payment. On this point, Gan Mor of The Venus Project’s Israel team says: “Albert Einstein didn’t invent the relativity theory to make money. The Wright Brothers didn’t invent the plane to make money.”[3] Indeed, great innovators often are driven by values and goals other than growing their wealth, but would it even be possible for them to do what they do without money?

In Fresco’s ideal society, these innovators would have access to everything they need to pursue their inventions, for free. But who would make the materials they need? Who would make their food? Who would operate and maintain the futuristic public transportation systems Fresco envisions whisking everyone and everything wherever they need to be faster and more safely than cars or planes? Einstein and the Wright Brothers had great goals to motivate them, but will the people doing those menial but essential jobs have any incentive to do them without reward?

Mor answers that we need to move away from the idea that people should have jobs at all. “Jobs were means to reach a certain goal in the past, before automation. We need to renew our thinking about all these concepts due to all the new information, and the new possibilities that have opened up to us in the modern era.”[4] Supposing machines will do all the menial work—who will build them? Who will maintain them? Who will repair them when they break down? Who will program them? These are questions that have no answer, because the entire idea of a world where people produce and maintain a flourishing society without a financial incentive is a total fantasy.

The “Post-Scarcity” Society

Fresco’s vision is based on the idea that technology will enable us to achieve an abundance, or “post-scarcity,” society—one in which there is so much of everything easily available that nobody need want for anything. It’s similar to the idea put forward by Gene Roddenberry and the other creators of Star Trek, which is set in a fictional Federation in which “replicator” technology that can create almost anything out of thin air has created a society where basic resources are essentially limitless (except the energy needed to power them). This, combined with humanity adopting a philosophy of self improvement over personal acquisition of wealth, has led to a moneyless society. As Captain Picard says in the Next Generation episode “The Neutral Zone,” “People are no longer obsessed with the accumulation of things. We have eliminated hunger, want, the need for possessions.” In the film Star Trek: First Contact he says, “The economics of the future is somewhat different. You see, money doesn’t exist in the 24th century. . . The acquisition of wealth is no longer the driving force in our lives. We work to better ourselves and the rest of humanity.”[5]

However, Star Trek’s references to this moneyless future are few and far between. They are completely absent from the original 1960s series and only occur occasionally from The Next Generation onwards. In contrast, the franchise is replete with examples of characters trading with the aliens and other humans outside the Federation to get things they need, other societies using money, and references in dialogue to paying for things and earning one’s pay. It seems as though characters reference it when the writers want to make a point about there being something more noble than desiring wealth, but avoid dealing with the practical implications of that in other stories.

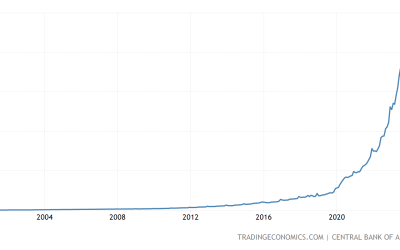

Like Maezawa, Fresco and the Star Trek writers are advocating what they think will be a better future, and some of their ideas are genuinely good. Picard’s point that we should “work to better ourselves” is a good one, as is Fresco’s understanding that technology is a good thing and that scientific and technological progress will improve our lives and free up more of our time for our own priorities. The fact that it is capitalism that has produced these technologies seems to pass them by. When Maezawa says “99% of people’s money is decreasing, but just 1% of people’s money is increasing,” he rightly takes issue with the fact that many people see the value of the money they save decreasing over time—a problem he should properly attribute to government-driven inflation, not capitalism. But would his moneyless solution, even if Fresco’s fantasy came true and it were practically possible, actually be a good thing?

Money and Rights

In advocating a moneyless society, Maezawa (a proponent of Universal Basic Income) and others are advocating a world in which there is no reward for productive effort—indeed, one in which there is a reward for not doing anything.[6] Yes, sometimes working toward and achieving a goal is reward enough by itself, but only when you’re working towards a goal you’ve chosen. What happens when personal goals don’t overlap with what needs to happen for society to keep functioning? What if nobody wants to repair and rebuild the machines that keep all the resources flowing? Money is not only a reward for people who work hard on projects they might still have done without it; it’s also an incentive to do work you otherwise wouldn’t have chosen to do, but that somebody needs done.

Most importantly, Fresco and company’s idea that all resources should be centrally allocated necessarily rests on the principle that the product of a person’s productive effort is not theirs to keep and decide how to use. Imagine you spend weeks or months working on a beautiful painting. Should somebody from the government be able to come and decide where that painting should hang? Should they be able to take it away and hang it in a public gallery for all to see, without you receiving any payment or having any say in the matter? Is that just? Moreover, Fresco claims that “all resources must be declared as the common heritage,” including intellectual resources, or as he calls it, “know-how.” Not only are the physical products of your work everybody else’s to use without payment, but your knowledge and skills are too.

Such a system also presupposes collective ownership of land, one of the “resources” Fresco wants to be freely available to all. If I want to use some land for a purpose the state doesn’t consider important but matters to me, such as building a museum about a niche interest, I couldn’t do that unless the state decided to permit me. I cannot buy land with the product of my productive effort—I cannot trade value for value with another person for it—I have to hope that those in power will let me use resources the way I want to.

“Social engineers” like Fresco think that their vision overrides the right we all have to decide how to live our lives, including how to interact with one another and how to use the things we produce. Fresco, like Maezawa, envisages a store where you go to collect, for free, the things you want. But who decides what’s in that store? If a business wants your money, they have to provide a product you want. Fresco’s central planners don’t have to pay your wants, or your rights, any heed at all.

Money, on the other hand, allows people to trade freely with one another and receive just reward for their work. It allows people to save resources for a later date, to invest, and to loan each other resources in a manner much more complex and suited to human needs and wants than a moneyless society or a barter system. Money is not, as Maezawa claims, the cause of war and crime. Wars generally happen when states, not content with violating the rights of their own citizens, seek the same power over people elsewhere, or when one group wishes to violate rights despite the opposition of another group. Crime (in a society with just laws) happens when individuals do not respect the rights of other individuals. Money is the means through which rights-respecting people trade freely and consensually with each other. It is the antithesis of force, the opposite of the mentality that leads to war and crime. This point is captured well in the speech “The Meaning of Money,” given by the character Fransisco D’Anconia in Ayn Rand’s novel Atlas Shrugged:

So you think that money is the root of all evil? . . . Have you ever asked what is the root of money? Money is a tool of exchange, which can’t exist unless there are goods produced and men able to produce them. Money is the material shape of the principle that men who wish to deal with one another must deal by trade and give value for value. Money is not the tool of the moochers, who claim your product by tears, or of the looters, who take it from you by force. Money is made possible only by the men who produce. Is this what you consider evil?[7]

Yusaku Maezawa should understand this well. He built his fortune trading with other people. He created businesses and innovations in the clothing industry that made better products easier to obtain. He improved people’s lives and they rewarded him for it. Moreover, he then used his wealth to go to space, an incredible thing to be able to do, and something he could only do because a private company, Space Adventures, sought to make a profit by charging him to fly with them. He has used money to benefit others and has benefited himself in return, and he has done both in ways that would be utterly impossible without the volume and complexity of trade money makes possible. For a productive man like him to advocate a moneyless system that would abrogate his rights and would have made his productive achievements impossible is truly shocking.

References

[1] “A ‘No-Money World’ and Things for Free? Japanese Billionaire Views Our Future from Space,” TASS, December 30, 2021, https://tass.com/science/1382773

[2] “A Global Holistic Solution: Resource Based Economy,” The Venus Project, https://www.thevenusproject.com/resource-based-economy/

[3] “Meet ‘The Venus Project’: The People Who Are Preparing for the Day When Money Will Be Meaningless,” The Venus Project, February 8, 2018, https://www.thevenusproject.com/meet-the-venus-project-people-preparing-for-the-day-when-money-will-be-meaningless/

[4] “A Global Holistic Solution: Resource Based Economy,” The Venus Project.

[5] “Money,” Memory Alpha: The Star Trek Wiki, https://memory-alpha.fandom.com/wiki/Money, accessed January 5, 2022.

[6] “A Japanese Billionaire Is Running a $9 Million Basic Income Experiment via Twitter,” Vox, January 13, 2020, https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/2020/1/13/21063764/basic-income-japan-yusaku-maezawa-andrew-yang

[7] Ayn Rand, Atlas Shrugged (New York: Signet, 1957), p. 380.