In The Wealth of Nations, published nearly 250 years ago, Adam Smith made a surprising statement:

“…The rate of profit…is naturally low in rich, and high in poor countries, and it is always highest in the countries which are going fastest to ruin.”

The Wealth of Nations, Chapter X, Part III, Kindle Edition.

Are profits higher in poor countries, and lower in rich countries? It would appear Smith had it backward. But he was no false prophet, as we shall soon see.

A recent Bloomberg headline trumpeted some seemingly good news: “Covid Can’t Stop Corporate Profits From Climbing To Record Highs.” The headline portrays a U.S. economy that has succeeded despite prolonged business closures, lockdowns, and mandates.

“U.S. corporations pulled in more profits in the three months ended in September than ever before. Not just in dollar terms—something that happens frequently—but as a share of the economy. According to initial estimates from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, third-quarter after-tax corporate profits from current production amounted to 11% of gross domestic product.”

What, other than pure business resilience, could have caused such good profit performance in the face of so much adversity? The reporter offers a half-hearted explanation, citing lower taxes and subsidies to business, but it’s clear from the article he’s not sure what’s really behind the profit boom.

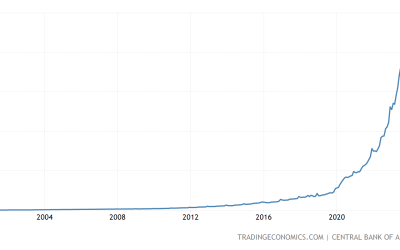

The reporter might have considered a different cause if he had looked at the graphs below, which document a near-parabolic 37% increase in the money supply beginning in March 2020, followed by soaring company profits starting six months later.

Does the unprecedented surge in the money supply have anything to do with swelling profits? The answer is a resounding yes, so let’s see why.

Source: U.S. Federal Reserve data

Source: U.S. Federal Reserve data

Intuitively, high profits seem like a good thing. Profitability is a crucial indicator of robust business health, so shouldn’t high economy-wide profits signal economic health?

Nope. Adam Smith, the Scottish founder of modern economic science, understood that high profit rates across an entire economy are not a good sign.

A mere glance will confirm there’s a heap o’ ruin in this here economy. Just this week, the Bureau of Economic Affairs confirmed what you already knew: consumer prices increased the most in over 40 years, spiking nearly 7% over the last 12 months. Meanwhile, Americans are leaving the workforce in droves (economists call it “the great resignation”) while supply chain issues threaten to spoil Christmas. Ours is not an economy firing on all cylinders.

But if the economy is not healthy, why is U.S. business so profitable? Where does all this profit come from?

Regular readers may anticipate the answer. These record profits came from the same excessive money creation that brought us other effects of inflation, previously documented in HardmoneyJim: soaring consumer prices, the record high cost of homeownership, and the impossibly high cost of saving. To this list, we can now add another pernicious effect of too much money creation: fake profits.

To see how an inflating money supply and fake profits are related, we must first acknowledge the timing relationship between costs and sales. In most cases, a company must invest capital and labor to produce something of value before selling the product. That’s the nature of the productive process. With a few exceptions, the outlay of money for production precedes the sale of the thing produced.

Next, we need to know the effect on prices when new money is injected into the economy. When new money enters the economy, the people who receive it spend some or all of it. Then it is re-spent again and again, raising the overall level of spending as it spreads through the economy. All else equal, prices will be higher after the injection of new money than before the new money came into existence. This principle is a simple expression of the quantity theory of money, which says the general price level depends primarily on the quantity of money available. All else equal, the larger the amount of money injected into the economy, the higher prices will rise.

Thus, during a highly inflationary period like the one we are in, the general price level will increase between the time a company spends cash for production and when it sells the product. Inevitably, these elevated prices will amplify profits.

A simple example will make this point clear. I’ll first present the explanation in narrative form, then summarize with the numbers at the end. Warning: arithmetic ahead. Grab a cup of coffee (or a cocktail) and read on.

Suppose a store owner – we’ll call him Sam – typically buys inventory in January, then sells it in December. By selling, he recoups enough money to pay his taxes, earn a profit to provide for his family and buy new inventory to sell in the following year.

Under a stable price environment, Sam pays 100 in cash for inventory in January and sells it in December for 110. After paying a 30% tax rate on his income of 10, he has total cash in hand of 107 (total sales proceeds of 110 minus taxes of 3). Sam has now recovered all his investment (100) plus a profit (7), so he’s able to buy inventory to make money again next year. He has paid the government its due, and he has a profit of 7 to sustain his family. Under stable prices, he can repeat this process year after year.

But Sam’s business looks very different during an inflation shock, as shown in the table below under the column titled “10% Annual Inflation.”

Imagine that after Sam bought his inventory for 100, the government comes along and mails big checks to all his customers. Flush with cash, these customers bid up the price of everything by 10%, so merchandise that would have sold for 110 now sells for 121 (110 x 1.1 = 121).

On pre-tax profit of 21 (121 – 100) Sam pays tax of 6.3 (30% x 21 = 6.3) leaving a profit of 14.7 (21 – 6.3 = 14.7).

So Sam now has after-tax profits of 14.7 (up over 100% compared to “stable prices”) and total cash in hand of 114.7 (total sales proceeds of 121 minus taxes of 6.3).

Wow, Sam’s after-tax profit more than doubled under inflation, from 7 up to 14.7. Maybe he should run out and buy a new car!

But if Sam is happy about this, he’s been tricked. Over the year, the price of everything has gone up 10%, so the cost of new inventory is now 110, not 100. (100 x 1.1 = 110). Sam now has to take 10 out of his after-tax profit of 14.7 to have enough money for new inventory, leaving him only 4.7 to live on during the year. (14.7 – 10 = 4.7). Compared to stable prices, Sam’s income goes down 2.3 (7-4.7), a decline of 33% (2.3 / 7 = 33%).

That’s bad, but it gets worse. Because the price of everything went up 10%, the 4.7 in cash will only buy 90% of what it would have purchased under stable prices. So Sam’s “real” profit shrivels from 4.7 to 4.2, for a total reduction of 40% in his standard of living. (.90 x 4.7 = 4.2).

Soaring profits are making Sam very poor.

This surprisingly unhappy outcome is due solely to inflation caused by the government’s massive injection of money over a short period.

Pro-business talking heads, perhaps like the Bloomberg reporter, think that because innovative businesses earn high profits, economy-wide high profits are a sign of general prosperity. Anti-business critics like Senator Karen (er, Senator Elizabeth Warren) have another view, believing high profits are the product of corporate greed, and high economy-wide profits mean the greed has gone viral. But in an inflation shock, neither of these explanations are true. Instead, it’s money creation, caused by government “stimulus,” that adds a big fake component to profits and may reduce real profits.

Record profits are not the sign of a resilient economy but an inflationary effect of reckless money creation caused by the government. Perhaps this sad state is what Adam Smith had in mind when he said high profits are not a sign of prosperity but an economy going fast to ruin.

I am indebted and grateful to George Reisman, Ph.D., for explaining the effect of inflation on profits and highlighting Adam Smith’s insight. I recommend all readers study his work “Capitalism: A Treatise On Economics.”